- Home

- Norris, Laurie Glenn;

Found Drowned Page 3

Found Drowned Read online

Page 3

The boys ran out of the barnyard.

“Us too?” asked Jimmy.

“No, you stay here,” Catherine said, grabbing her son by the shoulders.

“But Ma, we found her, it’s not fair.” Jimmy struggled to get away.

“You stay with your mother,” Gilbert said firmly. “We don’t need a bunch of kids running around down there.”

“But we have to show you where she is,” Tom protested.

“You can come along,” Neill said, “but you’re not going near it, whatever it is.”

Catherine grabbed Jimmy by the arm and started to walk towards the house. He kept looking back and yelling, “No fair.”

“Do like your mother says,” Gilbert ordered.

“You come in the house with me.” Catherine led him away.

Gilbert finished harnessing the horse and jumped on the wagon seat with Neill and Tom.

“Wait till you see, Pa, wait till you see.” Tom could scarcely contain his excitement.

“Sit still, you,” Neill warned him.

It took twenty minutes for the wagon to make its way along the path from the barnyard to the bank overlooking Bell’s Point.

The twins were waiting at the edge of the bank.

“Didn’t need Tom after all,” said Avard, pointing to the seagulls gathered down the beach.

“Run and get them out of there. Put the rocks to ’em,” Gilbert commanded.

“You stay in the wagon,” Neill said to Tom as he jumped to the ground.

“Aw, Pa.”

“Do as I say. No backtalk.”

“Yes, sir.” The boy crossed his arms and lowered his head in resignation.

In minutes, Avard and Eddie had chased the gulls away and stood over the spot.

“Yeah, it’s a girl,” Eddie shouted. “And you smell her before you see her.”

The sun from the cloudless sky cast shimmering light on the table top-smooth water. The crashing waves that, the night before, had tossed large pieces of driftwood ashore and cast sea spray on windows more than a mile away, were now gone. Seaweed lay like a woman’s necklace where it had been deposited along the bottom of the bank. When Gilbert and Neill got to the beach the smell hit them. Neill put his hand over his nose.

“You two stand back,” Gilbert barked at his sons.

The men bent over the figure. It reminded Gilbert of a discarded puppet, all loose and disjointed. The girl was lying on her left side, her face to the sky. Her legs were spread wide as if she had been running and then frozen to the spot. Her right arm was stretched out behind. The top joints of three of her fingers were missing. Her left arm was hidden beneath her. A plaid skirt and chemise were wrapped around her waist. She wore a black and white stocking on her right leg; the other limb was bare. She smelled of salt and rot and dead things.

“Av, get me a couple of those blankets from the wagon,” Gilbert said softly.

He covered the girl from the waist down with one of the horse blankets. Holding the other blanket in his left hand, he picked up a stick of driftwood with his right and folded the matted blond hair up over the top of her head. Throwing the stick aside he reached down again, his right hand covered by his shirt cuff and, running it over the girl’s face, closed her eyelids. There was a large clot of blood on the right side of her face. Hundreds of flies moved through it, some getting stuck and mired down. Bits of flesh around her left eye had been torn away by the gulls and something had nipped at her nose and chin. Bile rose in Gilbert’s throat. He stepped back quickly and spread the second blanket over the first, covering the rest of the body. He turned to Neill, silent beside him.

“Let’s get her into the cart and up to the barn. We’ll have to send for the sheriff.”

They carefully folded the blankets around the underside of the body as they lifted, not wanting to touch flesh, and then moved slowly up the bank towards the wagon. The girl was small but heavy and they couldn’t keep a firm grip on her. One limp arm escaped.

“What are we going to do with her, Pa?” Avard asked.

“We’ll have to put her in the barn for the time being,” Gilbert said as he and Neill carefully placed their bundle into the back end of the wagon.

“Tom, you run ahead and let Mrs. Bell know we’re coming,” Neill suggested.

“Yes, sir.”

Gilbert turned to the older boys. “And you two run over to Muttart’s and get the Captain to wire over for Sheriff Flynn,” he instructed. “Tell him that we found a dead body on the beach, and he better get out here and be damn quick about it.”

***

At seven o’clock that evening, Doctor Henry Jarvis drove his shiny black phaeton down the lane to the Bells’ farm. Men and boys milled about the barnyard or stood with arms crossed, leaning up against wagons and carts. They had already been inside the barn to look at the body but no one knew the girl. Now most of them were smoking and drinking tea from blue and white tin mugs. A few passed a flask back and forth. They looked up expectantly as Jarvis drove into the yard. Some waved their hands while others nodded in acknowledgment.

Jarvis grabbed his satchel from the floor of the vehicle and walked towards the middle of the group. He was a tall, spare man with thinning brown hair and grey side whiskers. He walked with a slight stoop which gave him a defeated look. His hazel eyes, nonetheless, snapped with a quick intelligence. A barrel-chested man walked out of the group and approached him, extending a calloused right hand.

“You the doctor?” the man asked.

Jarvis nodded. “I got a wire from Sheriff Flynn this afternoon about a body being found. I got here as soon I could.”

“I’m Gilbert Bell. I expected to see Doc Price from Charlottetown,” he said, inclining his head towards the barn.

“No, I’m the coroner for Prince County now.”

“So where’s Flynn?” Gilbert asked.

“I don’t know. I thought he’d be here by now.”

“Hasn’t been any sign of him yet. Anyway, she’s in the barn. Nobody here knows who she is. Must be from away.”

“It’s a woman then,” Jarvis stated.

“A girl more like, not very old.”

A balding, chubby man with a monocle stepped forward and extended his hand to Jarvis.

“Doctor, nice to see you again. You’ll remember me. Hezekiah Hopkins, the apothecary from North Tryon. You’ll likely need me to assist as I did before. You remember I’m sure.”

“Yes, I remember. Thank you for the offer but I don’t require your services,” Jarvis told him, moving away.

The chemist let out an embarrassed cough and retreated back into the throng of waiting men.

Gilbert stepped on his cigarette butt then loped towards the barn to catch up with the doctor. The twins joined them as they reached the far end of the building.

“We put her in here,” Gilbert went on. “We don’t use it very much, just for storing tools and milk cans. Didn’t want her in the way and spookin’ the animals. Probably put the cows off their milking as it is. Animals can smell death a mile away.”

The body was laid out on a small wooden table and draped with blankets. Jarvis placed his bag on the floor then gently pulled back the covering to look at the girl’s face.

“The gulls picked at her a bit,” Eddie said.

Avard poked him in the ribs. Gilbert shot them a stern look.

“Yes, I can see that,” Jarvis said, holding the blanket up high on his side of the table, shielding the body from the view of the others.

“You know, I haven’t had my dinner yet this evening,” Jarvis said looking at Eddie. “Maybe Mrs. Bell or one of your sisters could make me a sandwich.”

“We ain’t got any sisters,” Eddie replied, kicking at the barn floor.

“Go and tell your mother to make the doctor here something to eat,” Gilbert

said, nodding in the direction of the house. Eddie was resolved to stay put. “Go on. And stay there until it’s ready.” The boy walked out the door, dragging his feet.

Jarvis lowered the blanket, picked up his brown leather bag, and placed it on the table. The metal clasp clicked open and he started to rummage around with both hands. Then he stopped and looked at Avard.

“Just realized that I’d like a nice, hot cup of tea and a few lanterns in here. It’s going to be dark soon, I’ll need lots of light.”

Avard looked at his father.

“You heard him.”

“Don’t do anything until I get back,” said Avard, bolting for the door.

Gilbert shook his head.

“Don’t let either of them back in,” Jarvis said.

“I won’t, they’ve seen enough for one day. And I’ll just step outside myself so you can get to work. I’ll bring in the lanterns when Avard gets them.”

Gilbert headed for the door.

“Can you read and write?”

Gilbert turned. “Yeah, some, why?”

“Then I’ll need you here with me for this.”

“What the hell for?” Gilbert backed up towards the door.

“I need you as my clerk to write down what I’m going to tell you. I need to have notes taken while I’m performing the examination. I’m too likely to forget something if I wait until later to write it down. If Sheriff Flynn were here I’d press him into service. But tonight you’re my volunteer.”

Jarvis took a yellow notepad and a stubby pencil out of his coat pocket and handed them to Gilbert.

“What about Hopkins out there? He knows medicine. Wouldn’t he do a better job?”

Jarvis grimaced. “I’ve dealt with him once before. He’d brag all over the province about what he saw. I don’t want him involved. Just write down what I tell you. You don’t have to look.”

Gilbert nodded and flipped open the notepad to a clean page.

“Write down the date, the time, and where we are right now, your farm, Cape Traverse, PE Island,” Jarvis directed.

The doctor removed his black topcoat, folded it, and placed it on a nearby milking stool. He returned to the table, rolling up his shirt sleeves. Tossing the blanket aside with a flourish, he bent over the girl and slowly ran both hands over her scalp, front and back, and along the top and side of her head.

“She has quite a cut over her right eye, doctor.”

“I see that.”

Jarvis took a pair of scissors from his bag and cut away the matted hair on the right side of the head. He poked an index finger into the hole.

“Looks like she got hit on the head, or hit something when she fell into the water,” he said softly.

Jarvis opened her mouth and peered inside. He poked a finger in and moved it about, stretching the face wide.

“She threw up.”

He stood upright and looked at Gilbert.

“Her lips, nose, and earlobes are eaten away quite a bit.”

“Yeah, it’s a damn shame. Like Eddie said, the seagulls got at her.”

“I closed her eyes when we found her,” Gilbert added. “It seemed the decent thing to do.”

“It was.”

The doctor reached down and pinched open the left eyelid then the right one.

“Ah huh.”

“What?”

“The right pupil is blown,” Jarvis said. “Look,” he offered, standing back and still holding the lid open.

Gilbert stepped carefully towards the table and peered into the girl’s pale face. He had forgotten that he didn’t want to see anything. This close, the smell of rot and seaweed was overwhelming.

“Yeah.” He swallowed. “What’s that mean?”

“It means that she got a good bump on her head at some point before death.”

Jarvis let the eyelid drop.

Gilbert suddenly remembered why he was there. “Am I supposed to be writing this all down?” he asked.

“In a few minutes. Good. Now.” Jarvis lifted a knife from his satchel and cut through the leather belt. He snipped the bottom of the plaid skirt along its right side seam with the scissors then tore it the rest of the way up with both hands. He lifted the body gently, snatched the garment from underneath, and handed it to Gilbert.

“Put these aside, the sheriff will likely want to see them.”

The girl’s greenish-white skin became pink in the light of the sunset streaming through the cobwebs of the barn’s tiny west window. Jarvis cut, then tore, the right side of her jacket and its underarm along the seam. He slid it off the body, then did the same with the shirt waist and chemise. Gilbert folded the sodden clothes and placed them in a neat pile on the floor.

The door handle rattled.

“Pa, let us in.”

Jarvis, pawing through his medical bag, looked up.

Gilbert tuned towards Avard’s voice.

“Pa, the door’s stuck, it won’t open.”

“That’s because I braced it shut. You two stay put for a while.”

“Eddie’s got the soup Ma heated up and I’ve got the tea, they’ll get cold.”

“Thanks, boys, just keep them out there for me. This won’t take long,” Jarvis called.

“What about the lanterns, sir?”

The doctor nodded. “Those I do need right now.”

Gilbert yelled out the door while patting his shirt pocket. “Go get those two we use for milking, and don’t forgot to bring some matches, I’m all out.”

“Yeah, okay,” said Avard, retreating.

Jarvis lifted a black cloth bundle from the depths of his medical bag. It was tied round and round with a light brown grosgrain ribbon. Studying the body, Jarvis methodically unwound the ribbon then placed the cloth on the table and unrolled it. Six small, ivory-handled blades, each held in place by grosgrain loops attached to the cloth, caught the fading light.

“My scalpels,” he said. “While we’re waiting for those lamps, here’s what I’d like you to write down.”

Clearing his throat he began, pronouncing each word slowly and stopping occasionally so Gilbert could catch up.

Outside, Avard and Eddie backed away from the barn and dropped the food and tea bundles on the ground beside the express wagon. Eddie started back to the house while Avard ran to fetch the lanterns. After they were delivered, he walked up to Neill McPherson and Rufus Dobson who were standing in the middle of the barnyard smoking. Rufus had a ring of flattened butts at his feet.

“Best you two wait out here with the rest of us,” he told Avard, resting his cigarette-free hand on the boy’s shoulder. “I don’t like looking at a dead body at the best of times. She reminded me a bit of my sister’s girl Ruby but she’s working in Cape Breton somewheres now so it’s not her. The way that some young girls act today, chasing after men, I’m surprised they don’t end up dead more often. Still it’s a damn shame. Did your father say how much longer they’d be? Lillian don’t like to be at home alone after dark.”

“No, Pa didn’t say.”

In the house, Eddie was answering questions as well.

“What, the doctor didn’t even stop to have a bit of tea?” Viola McWilliams, the Bells’ nearest neighbour, and the twins’ godmother, commented when Eddie reported to his mother that he and Avard had failed to deliver the food. “Can’t say I’d have the stomach for it either.”

Catherine and three women who had escorted their husbands to the Bell farm were seated around the kitchen table.

“Poor little thing.” Sarah McPherson shook her head and sunk her teeth into another cranberry muffin.

“Catherine, how are you going to sleep tonight with that poor soul lying in your barn?” Beulah Hopkins asked, then continued on before Catherine could answer: “I don’t see why Hezekiah couldn’t have been in there

with the doctor tonight.” She sniffed. “He’s a professional chemist and we came all this way so he could be of assistance.”

“I think it’s safe to say that the girl’s beyond a dose of physic now,” Sarah observed. Beulah sniffed again.

Catherine shot Eddie a warning glance. He turned his back on the table and bent down to pick up a piece of wood. He shoved it into the stove, then bolted, grinning, for the door.

***

“Subject is a young girl, approximately sixteen years old. Five feet, four inches tall, about one hundred pounds. Light brown hair and blue eyes. Head wound over right eye, approximately one inch in diameter and one half inch deep. Pupil of right eye dilated.”

Jarvis walked around the table.

“I’ll take those for a minute,” he said, removing the notebook and pencil from Gilbert’s hands.

He drew a circle under the handwriting, and inside that, a smaller circle which he shaded in with the pencil. He wrote the words “anterior of head” under the circles, then he handed back the notebook and pencil.

“Continuing dictation. Portions of the subject’s fingers, nose, and earlobes were bitten by fish and/or seabirds. Arms and legs scarred from time in the water. No broken bones or fractures.”

He paused again.

“Subject wearing black wool jacket and brown leather belt with a silver buckle, red, white, and black plaid skirt, white shirtwaist and chemise, one black and white striped cotton stocking.”

There was a tentative knock at the door.

Gilbert walked over, jerked the plank away, and opened the door a crack. Avard was there with a lantern in each hand. All heads in the yard turned towards the barn.

“Are they all still here?” Gilbert whispered hoarsely.

“They’re waitin’ to hear what the doctor says.” Avard shrugged.

He handed his father the lanterns and then dug into his shirt pocket for a box of matches.

“Too goddamn nosey, the bunch of ’em,” Gilbert said, slamming the door in his son’s face.

“Put one of those at the end of the table and the other on that peg over there,” Jarvis directed.

Gilbert positioned the lanterns then replaced the plank at the door and sat down on a barrel. The lanterns cast an orange glow over the girl’s skin. The pencil needed to be sharpened and Gilbert had forgotten his jackknife in the house. It was warm and humid in the barn.

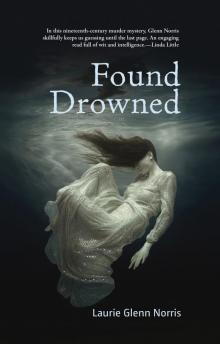

Found Drowned

Found Drowned