- Home

- Norris, Laurie Glenn;

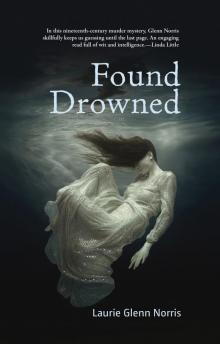

Found Drowned

Found Drowned Read online

Advance Praise for Found Drowned

“A body washing ashore opens up a Pandora’s box of ugly secrets in Laurie Glenn Norris’s historical whodunnit. Set in the late nineteenth-century Maritimes, Found Drowned exposes the underbelly of rural life in scenarios rife with family feuds, domestic abuse, and madness. With its near-forensic attention to detail, this suspense-filled tale rubs away the blush of romanticism which often tints views of our past. Think the Age of Sail with a macabre twist.”

–Carol Bruneau, award-winning author of A Circle on the Surface

“We’re gripped by the plight of Mary Harney, a spirited young woman who goes missing. Is she escaping from her bedridden laudanum-soaked mother—or from the oily grasp of her raging father? In Found Drowned, the action, the characters, the trains and towns and waterways all captivate us— drawn with compelling nineteenth-century detail.”

–Linda Moore, author of Foul Deeds and The Fundy Vault

“Few shadows from our collective past are as engaging and captivating as a good maritime Victorian murder mystery. In Found Drowned, Laurie Glenn Norris weaves a wonderfully mesmerizing tale of compelling characters caught in the darkest of miasmic uncertainties. Drawn into a time and place both warmly familiar yet coldly disturbing, readers will be unable to turn away from this skilfully told tale until reaching its surprising and satisfying finish.”

–Steven Laffoley, author of The Halifax Poor House Fire and The Blue Tattoo

“Fortune is a strumpet. Laurie Glenn Norris leads us along a murky path strewn with bad luck, or good, depending on the angle of approach. In this nineteenth-century murder mystery Glenn Norris skilfully entangles our assumptions with the facts and keeps us guessing until the last page. This is an engaging read full of wit and intelligence.”

–Linda Little, award-winning author of Scotch River and Grist

To Maureen, my only sister

Copyright © 2019, Laurie Glenn Norris

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission from the publisher, or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, permission from Access Copyright, 1 Yonge Street, Suite 1900, Toronto, Ontario M5E 1E5.

Vagrant Press is an imprint of

Nimbus Publishing Limited

3660 Strawberry Hill St, Halifax, NS, B3K 5A9

(902) 455-4286 nimbus.ca

Printed and bound in Canada

NB1359

Editor: Kate Kennedy

Editor for the Press: Whitney Moran

Cover and interior design: Heather Bryan

This story is a work of fiction. Names, characters, incidents, and places, including organizations and institutions, either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: Found drowned / Laurie Glenn Norris.

Names: Glenn Norris, Laurie, 1957- author.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20189068590 | Canadiana (ebook) 20189068604 | ISBN 9781771087506 (softcover) | ISBN 9781771087513 (HTML)

Classification: LCC PS8613.L458 F68 2019 | DDC C813/.6—dc23

Nimbus Publishing acknowledges the financial support for its publishing activities from the Government of Canada, the Canada Council for the Arts, and from the Province of Nova Scotia. We are pleased to work in partnership with the Province of Nova Scotia to develop and promote our creative industries for the benefit of all Nova Scotians.

“Alas, then, she is drown’d?”

Hamlet, Act 4 Scene 7

Bell’s Point

Cape Traverse, Prince Edward Island

September 12, 1877

The boys threw stones at it as soon as they saw the form in the distance. At first, with the sun in their eyes, they thought it was likely a calf. Once in a while one would stray from its mother, fall over a bank somewhere, and be washed to shore in the tide, its coat stiff with salt.

The seagulls had spied it first, their heads bobbing up and down, mouths open. Some of them had already landed and started to pick. When the stones began to fall around them with hollow thuds, the birds reluctantly scattered.

“See, I told you it wasn’t no animal,” Tom said as they got closer.

Jimmy ran on ahead of his friend.

“It’s a girl,” he yelled, dropping to his knees before the entangled figure.

“Jesus, don’t get that close, Jim, you don’t want to catch nothin’ off her. Don’t touch her!”

Tom backed away.

Leaning forward, Jimmy extended one chubby fist and lifted a clump of blond hair. A pair of blank, blue eyes stared back at him.

“She’s dead as a doornail,” Tom yelped, backing up again.

“Let’s go git Dadda.”

The boys ran across the beach and scrambled up the bank, their bare feet leaving tracks in the shiny red mud, while the screeching gulls descended once again.

The life I carried was like a tiny fish encased in its own personal sea.

Merigomish

Nova Scotia

August 1876

Mary watched Rachel scrub Grandma Hennessey’s kitchen floor. Rachel Connelly had been with the family for six months now, one of two housemaids the Hennesseys employed, along with Susan the cook.

“She’s practical and clean,” Helen Hennessey told her husband Patrick after she hired the girl.

Mary and her mother, Ann, with Little Helen, age four, and Harry, one and a half—“the two little ones,” as Ann called them—were visiting Merigomish from Rockley for a fortnight. It was the first trip back home for Ann since she was a bride. The Harney children had never met their grandparents or Aunt Beatrice. Mary, almost seventeen, was especially shy around them even though she adored her aunt as soon as she laid eyes on her. The kitchen became one of Mary’s favourite places to linger, however, and Rachel her confidant.

“Are you going to get married some day, Rachel?” she asked.

“I sure hope so. I don’t wanna be scrubbing somebody else’s floors all my life. Even though Mr. and Mrs. Hennessey are good to me,” she hastened to add. “I know I’m some lucky to work here.”

Rachel stopped to tidy the wisps of curly red hair that kept creeping out from under her dust cap. She was a short, big-boned girl with a creamy complexion, freckles on her nose, and strong forearms. Whenever she leaned across the top of the metal bucket to wet the floor, her pendulous breasts nearly filled its circumference.

There were lots of young men around who admired Rachel Connelly; she was not worried about ending up an old maid.

“I don’t want to,” Mary proclaimed with a defiant shake of her head.

“Every girl wants to be married.”

“I don’t.”

“How come?”

Mary shrugged. “I just don’t. I want to be by myself.”

Rachel smiled. “People will make fun of you for being an old maid. And you’ll have to live with your mother and father.”

“No, I won’t.”

“And babies, don’t you want to have your own babies?” Rachel continued. “I’m going to have three boys and then three girls. Boys should always be the oldest so that they can help their father out on the farm as soon as they can.”

“I’d like to have babies but not a husband.”

“It doesn’t work that way, Mary.” Rachel shook her head and whispered: “To get the babies, you need a husband or you’d be ruined. That’s what happened to my cousin Agnes, she…no, never mind.”

&nbs

p; “Tell me?” Mary leaned forward in her chair.

“No, your grandmother would show me the door if I talked to you about such things.” Rachel bent over the wash bucket once again.

“Do you ever feel all wrong?” Mary asked.

“What do you mean?”

“Do you ever feel like no matter what you do or say, that you’re in the wrong, that other people are always right and you’re always wrong, about everything? I can’t seem to do anything right.”

“Well, at home I’m the oldest and the only girl. So I’m usually right. Pa is always telling my brothers to mind what I say.”

“I’m always the wrong one in my house,” Mary told her.

“Who says?”

“Daddy and Grandma Harney. And Mumma agrees with them.”

“I find that hard to believe.” Rachel snorted.

“It’s true. Grandma Harney says it all the time and Mumma doesn’t say any different.”

Tears welled up in Mary’s eyes.

“Lots of women don’t like to disagree with their husbands to their face and if you don’t mind my saying so, your ma’s a bit on the timid side, so I can’t image her talking back to Mr. Harney at all, not that she should.”

Rachel took a handkerchief out of her apron pocket and handed it to Mary, who buried her face in the clean cotton.

“Your ma has two babies to look after besides your father. You’re getting older now and it’s your place to help her all you can.”

“I know,” sighed Mary.

She wiped her face, blew her nose, and presented Rachel with the crumpled cloth.

“Look,” said Rachel, cramming the handkerchief back into her apron pocket, “I’m just about done here. Wait till I scrub us out the door and then you can come and watch me bring in the clothes. It’s been a good drying day and I’m sure they’re about ready to come in. Then I’ll have to help Susan get supper on.”

“All right.”

“I just love a nice clean floor,” Rachel said, smiling. “Ma always told me that clean floors make a house feel warmer in the winter and cooler in the summer.”

You know,” she continued, “I lost my ma almost six years ago. She was so sick and she’s better off now but life’s not the same without her. Keep that in mind. You’re lucky to still have your mother.”

Mary nodded and wiped her eyes with the sleeve of her dress.

After Rachel wrung out the mop and threw the dirty water into the long grass at the side of the house, she and Mary walked towards the clothesline.

***

The Hennesseys’ house sat close to the main road. Its yellow paint was new, just put on last year, and pink and white geraniums sat in clay pots in each of its five front windows, shown to advantage against the white shutters and crisp curtains. The three large hay barns, cow shed, stable, and numerous outbuildings sprouted up behind the house. It had taken Helen Hennessey twenty-five years, but finally the backyard was a tangle of shrubs and flowers surrounding whitewashed benches, reflecting globes in the cutting garden, and numerous feeders for blue jays, mourning doves, and hummingbirds.

When Mary wasn’t spending time with Rachel, she was following her Aunt Beatrice and Grandma Hennessey around the house. Beatrice promised to make Mary and Little Helen each a new dress. She had started Mary’s already from a pattern for a day dress in Godey’s Ladies Book. Beatrice had made the same one for herself only three months before in navy blue. Mary’s dress was to be lime green with black collar and cuffs and green buttons down the front. It would be her first ever grown-up dress and a change from the two blue frocks and aprons—one for school and the other to do her chores—that she wore all the time. She did have a cotton shirtwaist and a plaid skirt that she wore, summer and winter, to church, but they were quite worn. Now she would wear them for everyday and have something new for Sunday that would make the eyes of those LeFurgey girls bug out even more than usual. It was going to have a bustle in the back, Mary’s first bustle, and a new lace-bordered petticoat and it would be long enough to skim over the tops of her boots, just like a proper young lady. She couldn’t wait to wear it.

Like Mary, Ann had two dresses that she wore over and over. When she complimented Beatrice on her new pink walking suit, Grandpa Hennessey piped up, “You could have had clothes like that today too if you’d been smart.”

Grandma Hennessey shushed him and he went back to reading the Eastern Chronicle. Later that day, Beatrice had gone through her things and given Ann two morning dresses and a walking suit, all in pretty jewel colours. Most of Ann’s clothes were black and white.

“She looks like a damn Quaker,” Grandpa snorted.

Aunt Beatrice was thirty-five years old and an old maid but she didn’t seem to mind a bit. In fact, she said she preferred it that way.

“Life is short. I want to do all the things I can now. Looking after and catering to a man would only get in the way,” she told Mary, who had asked her about it one day when her aunt was fitting the dress sleeves.

“I feel the same way, Auntie,” Mary declared. “And I don’t like men,” she added.

“There’s nothing wrong with men. I just don’t want to live with one. Papa’s more than Mother and I can handle as it is.”

She looked over at her sister, who was at the kitchen window washing Harry’s face for the fourth time that morning.

“But one thing I do regret is not having a child. I could eat the three of you up, you’re all so sweet.”

“Don’t let them fool you, Bea. They’re not as nice as they look.” Ann grinned, drying Harry’s face and tapping his backside as he ran away giggling.

“Sure they are,” Beatrice said, bending down, touching her cheek to Mary’s, and enveloping her niece in the scent of lavender. “Now stand straight, Mary, and let me try to fix this sleeve.”

“This is too much, Bea,” Ann said. “And that dress is too old for Mary.”

“Oh pooh, Annie. You’ve kept Mary in children’s clothes far too long. She’s a young woman now and needs some nice things to call her own.”

“I don’t want her growing up too fast,” Ann replied.

“Now go take that off again, sweetie, and I’ll just stitch it up on the machine.” Beatrice pinched her niece’s cheek. “Oh, wait a moment. I want you to step on this piece of paper, so I can trace around your feet.”

“Why?”

“Just for fun, to compare the size of your feet with mine. Good, now off you go.”

Mary thought that Beatrice had the most interesting things. A Singer sewing machine that always smelled of the oil she doused it with, cardboard slides of side-by-side photographs that became one picture when you looked at them through a fancy viewer, and all the latest books and magazines. Along with Godey’s she had both the Canadian Illustrated News and the London Illustrated News delivered by mail twice a month. And at the moment she was reading a new book just purchased from a Halifax bookstore. It was a collection of short stories entitled Doctor Ox, written by a man called Jules Verne. Best of all, she’d been reading The Woman in White, by Wilkie Collins, aloud in the library every evening once Little Helen and Harry were put to bed. Grandpa called it trash but Mary, Ann, and Helen hung on every word.

“That Sir Percival is up to no good, I just know it,” Helen said looking up from her rug-hooking. “Why did poor Laura ever marry such a scoundrel?”

“Why indeed,” Grandpa said, raising his eyebrows at Ann.

Grandma spoke softly, barely above a whisper, but Grandpa, Beatrice, and Ann minded her every word. She and Grandpa seemed to know what the other was thinking and sometimes even said the same things at the same time.

Grandma and Beatrice visited places like San Francisco and Boston and London, England, and sent Ann, Mary, and the little ones beautiful postcards, photographs, and gifts, wherever they went. But they had never been to Ann�

�s home in Rockley.

Early in the morning on the day that the Harneys were to return home, Beatrice crept into Mary’s and Little Helen’s bedroom. The girls were still asleep and she put two brown paper bundles at the bottom of their bed. A half hour later the family was gathered around the breakfast table when they heard two squeals and then laughter. Shortly, there was clomping on the stairs and landing and Mary and Little Helen burst into the kitchen, still in their night dresses, with new boots on their feet.

“It’s just like Christmas.” Mary laughed.

“Like Quismis,” Little Helen echoed.

The girls danced around the table holding hands and looking down at their feet. Little Helen’s boots were shiny black leather with gold buttons up the side. Mary’s were a white and black gingham pattern with black buttons and soles.

“Bea, this is too much,” Ann said.

“Auntie! We knew it was you.”

The two girls fell upon Beatrice, Little Helen hugging a knee while Mary wrapped her arms around her aunt’s neck.

“What did Harry get?” Mary asked.

“Look on the sideboard.”

There was a blue outfit with short pants, a coat, and a round-billed cap for the toddler.

“Oh sweet,” said Mary.

“Ohhhhh swee,” said Little Helen.

“Mary desperately needed a new pair of boots, boots that a young lady would wear, and I wanted to make sure that everyone had a goodbye gift.” Beatrice smiled and lifted Little Helen up onto her knee.

“I’m sad to be going away,” said Mary. “I wish we could stay longer.”

“Yes, I know, dear. We all wish you could,” said Helen touching her cheek.

“Could I?” Mary asked, looking shyly from her mother to her grandmother.

Found Drowned

Found Drowned